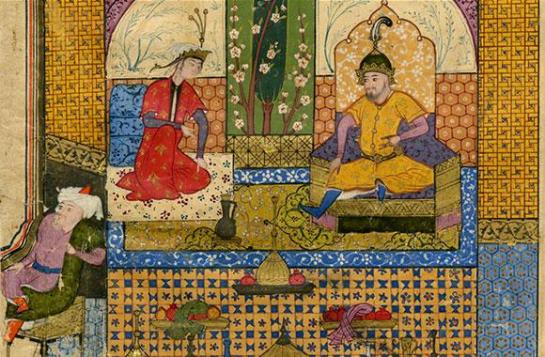

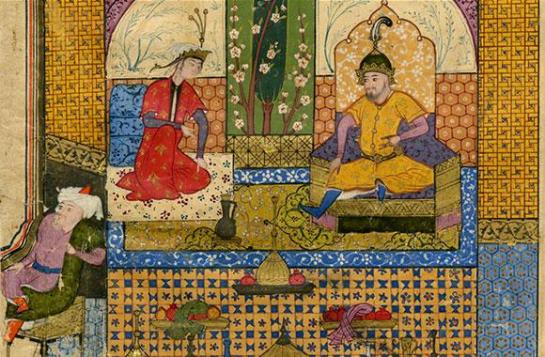

Detail of a page (c. 1580) from Minassian Collection, a database of Persian, Mughal, and Indian miniature paintings at Brown’s Center for Digital Scholarship.

Here’s a great Watson Institute write-up about our 2013 conference, by Samuel Adler-Bell. Thanks to Sarah Baldwin-Beneich.

Digital Humanities and Middle East Studies

New Methodologies for Old Texts Raise Eyebrows

Last month “The Digital Humanities and Islamic and Middle East Studies” conference at the Watson Institute brought together scholars from a range of disciplines to examine the effect of new digital archiving and research technologies on the study of Islamic and Middle Eastern history and literature. And it might never have happened if it weren’t for renowned Islamic historian Michael Cook’s eyebrow.

In 2004, conference organizer Elias Muhanna was a graduate student in Professor Cook’s famously difficult history methodologies seminar at Princeton. Muhanna, who is now assistant professor of comparative literature and Middle East studies at Brown, was spending, as he put it, hours upon hours in the “depths of Princeton’s Firestone Library poring over 19th century editions of long forgotten compendia by minor authors in godforsaken locations of the medieval Islamic world” and often still failing to find the answers to Cook’s arcane historical puzzles. The course was, in Muhanna’s words, a “trial by fire,” a sink or swim tutorial in the esoteric methods of deep archival research.

But at a certain point in the middle of the semester, something changed. Muhanna and his colleagues began finding the answers to Cook’s questions, but in unexpected places, locating references to Cook’s citations in works that he had not consulted. It was at this point, Muhanna says, that Cook raised his eyebrow suspiciously. Cook’s students had discovered the utility of the enormous textual databases of classical Islamic sources that had, in 2004, just been made available online. “We had found the answer,” says Muhanna, “using a kind of search and capture method … and not in the very tortuous way he was hoping to make us get it.”

This experience, says, Muhanna, was one of the impetuses for last month’s conference, which is part of a larger research initiative hosted by the Middle East Studies program. Michael Cook’s raised eyebrow represents an ambivalence at the core of the digital humanities, perhaps especially as they relate to the study of the Islamic world. Digital archives, text-searchable databases, computational analyses, these innovations have reshaped the methodological landscape and opened a door to new and exciting research. But for scholars of Islamic history and literature who have come to see the long, tortuous work of archival research as commensurate with the discipline itself, the digital humanities have been met with more than a few raised eyebrows.

“I felt that there was something tremendous to be gained by this technology,” Muhanna said in his opening remarks, “but there was also something probably tremendous that was in danger of being lost.”

Although this ambivalence may have inaugurated the conference, the vast majority of work presented by attending scholars attested, unambiguously, to the rich new world of research questions provoked by combining digital innovations with Islamic and Middle East studies scholarship. For example, for her project on “The Geography of Readership in Early Modern Istanbul,” Harvard historian Meredith Quinn compiled a database of probate inventories from 17th century Istanbul, paying special attention to those that listed books among the possessions of the deceased. Using quantitative analysis, she worked to identify correlations among book ownership, gender, class, and occupation. She then integrated that data with a map of the city to identify the more “bookish” neighborhoods of 17th century Istanbul.

Projects like Quinn’s, which elegantly combine archival sources with digital mapping and quantitative analysis, are so natural, grounded in good research, and plainly productive of new scholarly knowledge and questions, that any resistance from the digital humanities skeptics seems misguided: purist methodological traditionalism. Or worse, the resentful Luddism of a generation of scholars who “had to do it the hard way, so why don’t you?” On the other hand, one can more easily understand humanists chafing a little at the title of Bryn Mawr graduate student Alex Brey’s algorithm-dependent presentation on “Quantifying the Qur’an,” despite the fact that it addressed core issues of humanist concern, such as book history and scribal practices.

Professor Muhanna notes that scholars in the digital humanities might occasionally have a romantic, emotional, or religious reticence about converting a sacred text into points of data to yield historical knowledge. “There’s an understandable resistance to construing the tremendously complex object of one’s research, whether that’s a literary or a religious text, as basically a corpus of data. It has the association that it becomes just ones and zeroes.” And even more resistance about “the idea that we can somehow perform complicated analytical operations that might replace the very careful, painstaking work of interpretation.”

A self-critical debate over the proper scope of the digital humanities popped up at various moments throughout the conference. “Is this a new paradigm?” Muhanna asked, “Does digital, data-driven scholarship tell us anything qualitatively new? Or does it just give us these tremendous tools to confirm what we already intuitively know, and that we had already arrived at through old-fashioned interpretative scholarship?”

At some point during one of these self-reflective flare-ups, one scholar remarked, somewhat pugnaciously, “So we’re historians with computers. That’s enough for me!”

Muhanna’s conclusion is somewhat more nuanced: “The best way to think about it is that we’re just dealing with different sets of questions. And that one set doesn’t invalidate the other set.”

– Sam Adler-Bell